What was the transatlantic slave trade?

“The transatlantic slave trade was an oceanic trade in African men, women, and children which lasted from the mid-sixteenth century until the 1860s. European traders loaded African captives at dozens of points on the African coast, from Senegambia to Angola and round the Cape to Mozambique. The great majority of captives were collected from West and Central Africa and from Angola. The trade was initiated by the Portuguese and Spanish especially after the settlement of sugar plantations in the Americas. European planters spread sugar, cultivated by enslaved Africans on plantations in Brazil, and later Barbados, throughout the Caribbean. In time, planters sought to grow other profitable crops, such as tobacco, rice, coffee, cocoa, and cotton, with European indentured laborers as well as African and Indian slave laborers. Nearly 70 percent of all African laborers in the Americas worked on plantations that grew sugar cane and produced sugar, rum, molasses, and other byproducts for export to Europe, North America, and elsewhere in the Atlantic world. Before the first Africans arrived in British North America in 1619, more than half a million African captives had already been transported and enslaved in Brazil. By the end of the nineteenth century, that number had risen to more than 4 million. Northern European powers soon followed Portugal and Spain into the transatlantic slave trade. The majority of African captives were carried by the Portuguese, Brazilians, the British, French, and Dutch. British slave traders alone transported 3.5 million Africans to the Americas.”[1]

“The Transatlantic Slave Trade,” Black History in Two Minutes, November 13, 2020, https://blackhistoryintwominutes.com/2020/11/transatlantic-slave-trade/.

What was the Middle Passage and the Triangular Trade?

The Middle Passage was the forced physical voyage of enslaved Africans in slave ships across the Atlantic Ocean to colonial North America, the West Indies, and Brazil. From 1514 until the mid-1800s, more than 12 million Africans made the 21-to-90 day voyage aboard overcrowded and diseased-ridden ships manned by crews from France, Great Britain, The Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain.[2]

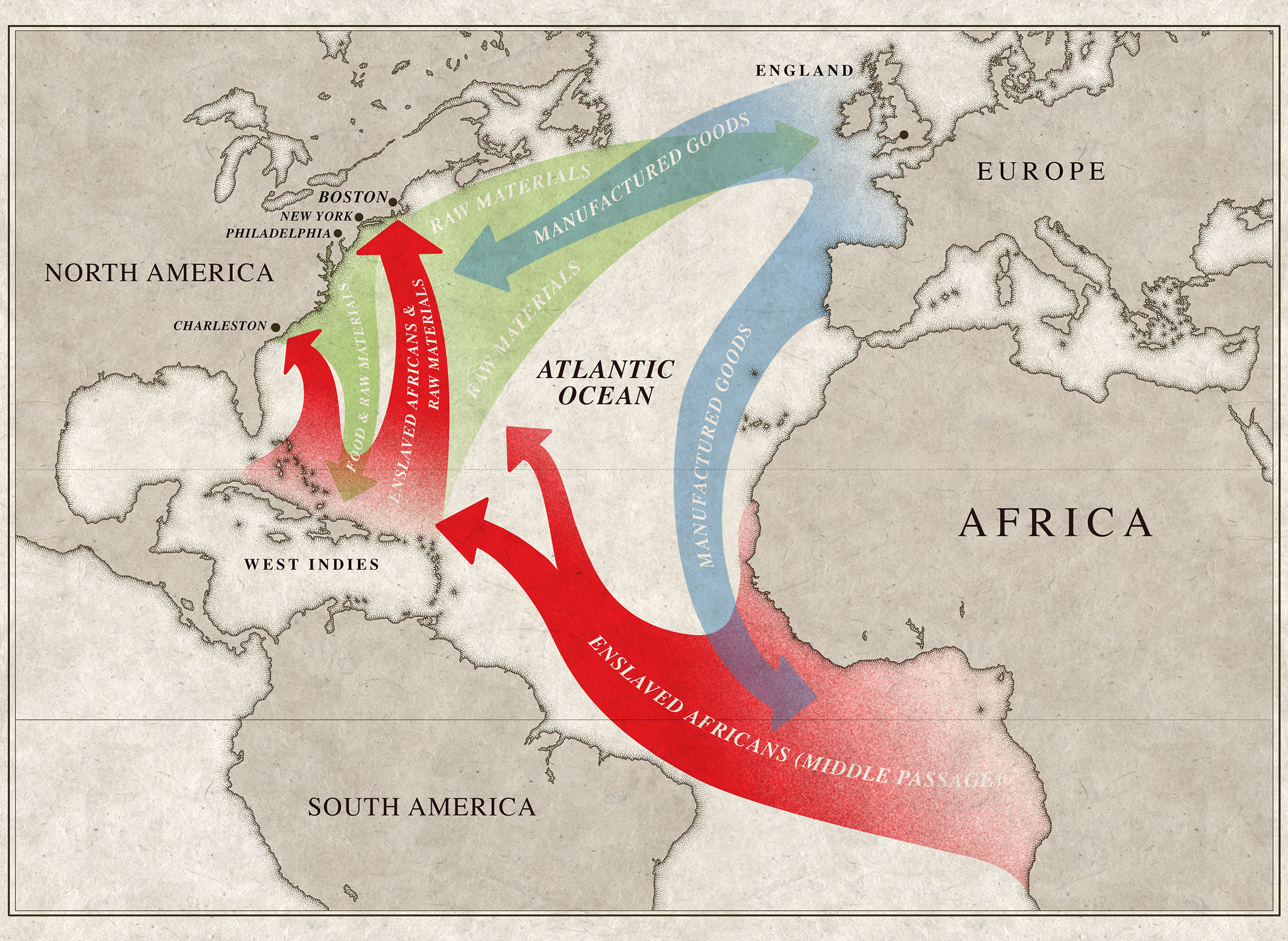

The Triangular Trade describes the pathways from European ports to Africa’s western coast and then on to the Americas. Manufactured goods such as ammunition and metals were exchanged for enslaved Africans. The second leg of this trade involved the transportation of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic Ocean, referred to as the Middle Passage. Upon arrival in the Americas, raw commodities such as sugar, rice, rum, tobacco, and later, cotton were loaded back on to the ships for the return voyage to Europe, the third leg of the Triangular Trade.[3]

National Park Service, Map showing the primary movement of Enslaved Africans, raw materials, and manufactured goods, https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-middle-passage.htm

What was the second Middle Passage?

“The second forced migration was known as the domestic, or internal, slave trade. . . . When we think of the image of slaves being sold ‘down the river’ on auction blocks — mothers separated from children, husbands from wives — it was during this period that these scenes became increasingly common. The enslaved were sometimes marched hundreds of miles to their destinations, on foot and in chains. Indeed, the years between 1830 and 1860 were the worst in the history of African American enslavement.”[4]

“Second Middle Passage,” Black History in Two Minutes, November 20, 2020, https://blackhistoryintwominutes.com/2020/11/second-middle-passage/.

How was slavery encoded in law?

“The use of enslaved laborers was affirmed — and its continual growth was promoted — through the creation of a Virginia law in 1662 that decreed that the status of the child followed the status of the mother, which meant that enslaved women gave birth to generations of children of African descent who were now seen as commodities. This natural increase allowed the colonies — and then the United States — to become a slave nation. The law also secured wealth for European colonists and generations of their descendants, even as free black people could be legally prohibited from bequeathing their wealth to their children. At the same time, racial and class hierarchies were being coded into law: In the 1640s, John Punch, a black servant, escaped bondage with two white indentured servants. Once caught, his companions received additional years of servitude, while Punch was determined enslaved for life. In the wake of Bacon’s Rebellion, in which free and enslaved black people aligned themselves with poor white people and yeoman white farmers against the government, more stringent laws were enacted that defined status based on race and class. Black people in America were being enslaved for life, while the protections of whiteness were formalized.”[5]

“Free Black Americans before the Civil War,” Black History in Two Minutes, April 15, 2022, https://blackhistoryintwominutes.com/2022/04/free-black-americans-before-civil-war/.

References

[1]“Transatlantic Slave Trade,” Slavery and Remembrance: A Guide to Sites, Museums, and Memory, accessed November 18, 2019, http://slaveryandremembrance.org/articles/article/?id=A0002.

[2]“The Middle Passage,” Boston African American Historic Site, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-middle-passage.htm.

[3]See David Eltis, “Interpretation: A Brief Overview of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade,” 2007, Slave Voyages, accessed November 18, 2019, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/essays#interpretation/overview-trans-atlantic-slave-trade/introduction/0/en/ and Stephen D. Behrendt, “Interpretation: Seasonality in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade,” 2008, Slave Voyages, accessed November 18, 2019, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/essays#interpretation/seasonality/introduction/0/en/.

[4]Henry Louis Gates Jr., “What Was the 2nd Middle Passage?” The Root, January 28, 2013, https://www.theroot.com/what-was-the-2nd-middle-passage-1790895016.

[5]Mary Elliot, “Four Hundred Years After Enslaved Africans Were First Brought to Virginia, Most Americans Still Don’t Know the Full Story of Slavery,” New York Times, August 19, 2019, accessed November 18, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/19/magazine/history-slavery-smithsonian.html. See also Paul Finkleman, “Slavery in the United States: Persons or Property?” in The Legal Understanding of Slavery: From the Historical to the Contemporary, edited by Jean Allain (Oxford University Press, 2012), 105-134, accessed November 18, 2019, https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5386&context=faculty_scholarship.